Assignment 8: Egg-eater: Arrays

Due: Thu 12/02 at 9pm

git clone

In this assignment you’ll extend to implement mutable arrays, which are sort like eggs lain in the heap, if you don’t think about it too much...

1 Language and Requirements

Egg-eater starts with the same semantics as Diamondback, and adds support for

array expressions: creating values, accessing components, and mutating components

sequencing of expressions

richer binding syntax

The runtime system must add support for

Allocating values on the heap

Printing array values

Comparing array values for structural equality

This is a large assignment, and its pieces are tightly interconnected. Read through the whole assignment below carefully, then take note of the recommended TODO list at the bottom for a suggested order to tackle these pieces.

2 Syntax Additions and Semantics

The main addition in Egg-eater is array expressions, along with

accessor expressions for getting or setting the contents of arrays, a

unary primitive for checking if a value is an array, and a unary

primitive for getting the length of an array. Array expressions are a

series of zero or more comma-separated expressions enclosed in

(square) brackets. An array access expression is one expression

followed by another enclosed in square brakcets, which expresses which

field to be accessed. isarray is a primitive (like

isnum and isbool) that checks if a value is an

array. Finally, length is a primitive that produces the

length of an array.

‹expr› ... let ‹binds› in ‹expr› ‹array› ‹expr› [ ‹expr› ] ‹expr› [ ‹expr› ] := ‹expr› ‹expr› ; ‹expr› isarray ( ‹expr› ) length ( ‹expr› ) ‹exprs› ‹expr› ‹expr› , ‹exprs› ‹array› [ ] [ ‹exprs› ] ‹destruct› IDENTIFIER [ ] [ ‹destructs› ] ‹destructs› ‹destruct› ‹destructs› , ‹destruct› ‹binds› ‹destruct› = ‹expr› ‹destruct› = ‹expr› , ‹binds›

For example, we can create three arrays and access their fields:

let unit = [] in

let one = [1] in

let three = [3, 4, 5] in

three[0]An array-set expression evaluates both arguments, updates the array at the appropriate index, and returns the entire tuple value as its result. We can therefore chain array-set expressions together, and write

let three = [0, 0, 0] in

((three[0] := 1)[1] := 2)[2] := 3

let pair = [0, 0] in

pair[0] := (three[1] := 10)three will be [1,10,3] and pair will be [three, 0]We can also actively destructure arrays when we bind them:

let t = [3, [[4, true], 5]] in

let [x, [y, z]] = t

x + y[0] + zx is bound to 3, y

is bound to [4, true] and z is bound to

5.Your check_prog function should ensure that

all variables in the same destructing let are distinct and raise a

DuplicateBinding error otherwise.

In the Exp datatype, these are represented as:

enum Exp<Ann> {

...

Array(Vec<Exp<Ann>>, Ann),

ArraySet {

array: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

index: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

new_value: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

Semicolon {

e1: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

e2: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

AssertSize(Box<Exp<Ann>>, usize, Ann),

}

enum Prim1 {

...

IsArray,

Length,

}

enum Prim2 {

...

ArrayGet,

}This includes an additional form which is purely internal to the

compiler: AssertSize, which asserts that an array has a given

length. This is used in the compilation of destructuring let.

In Sequential form, these expressions are represented as SeqExps, with ImmExp

components:

enum SeqExp<Ann> {

...

AssertSize(ImmExp, usize, Ann),

Array(Vec<ImmExp>, Ann),

ArraySet {

array: ImmExp,

index: ImmExp,

new_value: ImmExp,

ann: Ann,

},

}Note that these expressions are all SeqExps, and not

ImmExps – the allocation of an array counts as a “step” of execution,

and so they are not themselves already values.

To make the bindings work in our AST, we need to enhance our representation of binding positions:

enum BindExp<Ann> {

Var(String, Ann),

Arr(Vec<BindExp<Ann>>, Ann),

}

enum Exp<Ann> {

...

Let {

bindings: Vec<(BindExp<Ann>, Exp<Ann>)>,

body: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

}Let-bindings now can take an arbitrary, deeply-structured binding, rather than

just simple names. Further, because we have mutation of arrays, these act more

like statements than expressions, and so we may need to sequence multiple

expressions together. Further still, sequencing of expressions acts just like

let-binding the first expression and then ignoring its result, before executing

the second expression. In other words, e1 ; e2 means the same

thing as let DONT_CARE = e1 in e2 where DONT_CARE is a variable distinct from all others in the program.

To keep things simple, we will only allow these new binding forms in let bindings and not in function parameters.

3 Desugaring away unnecessary complexity

The introduction of destructuring let-bindings and sequencing make the rest of compliation complicated. sequentialization, stack-slot allocation, and compilation all are affected. We can translate this mess away, though, and avoid dealing with it further.

Nested let-bindings: Given a binding

let [b1, b2, ..., bn] = e in bodywe can replace this entire expression with the simpler but more verbose

let temp_name1 = e,

DONT_CARE = assertSize(e, n)

b1 = temp_name1[0],

b2 = temp_name1[1],

...,

bn = temp_name1[n-1]

in bodywhere assertSize is pseudo-syntax for our internal

assertSize form that ensures that the array has the given length.

(Note that the (n-1) in the last binding is not a literal subtraction

expression, but a compile-time constant literal integer, deduced solely from

the length of the original binding expression.)

If you destructre an array with the wrong length such as in

let [x, y, z] = [0, 1, 2, 3] in eYou should raise an error at runtime containing the message

"destructured wrong number of elements".

length(e) should evaluate its argument and return its

length if it is an array. If the input is not an array it should

display an error with the message "length called with

non-array".

Sequences:

You should implement a desugar phase of the compiler, which runs somewhere

early in the pipeline and which makes subsequent phases easier, by implementing

the translations described in this section.

Think carefully about (1) when to desguar

relative to the other phases in the compiler, and (2) what syntactic

invariants each phase of your compiler expects. You may want to enforce those

invariants by panic!ing if they’re violated.

4 Semantics and Representation of Arrays

4.1 Array Heap Layout

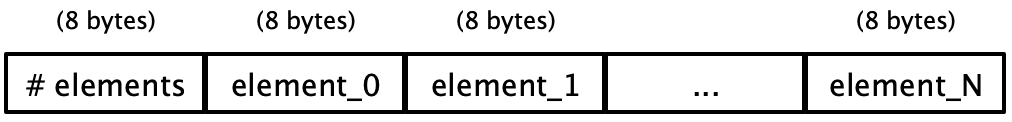

Array expressions should evaluate their sub-expressions in order from left to right, and store the resulting values on the heap. We discussed several possible representations in class for laying out arrays on the heap; the one you should use for this assignment is:

That is, one word is used to store the count of the number of elements in the array, and the subsequent words are used to store the values themselves. Note that the count is an actual integer; it is not an encoded Egg-eater integer value.

An array value is stored in variables and registers as the address of the

first word in the array’s memory, but with an additional 1 added to the value

to act as a tag. So, for example, if the start address of the above memory

were 0x0adadad0, the array value would be 0x0adadad1. With this change, we

extend the set of tag bits to the following:

Numbers:

0in the least significant bitBooleans:

111in the three least significant bitsArrays:

001in the three least significant bits

Visualized differently, the value layout is:

Bit pattern |

| Value type |

|

| Number |

|

| True |

|

| False |

|

| Tuple |

Where W is a “wildcard” 16-bit nibble and b is a “wildcard” bit.

4.2 Accessing Array Contents

In an array access expression, like

let t = [6, 7, 8, 9] in t[1]The behavior should be:

Evaluate the expression in array position (before the brackets), then the index expression (the one inside the brackets).

Check that the array position’s value is actually an array, and signal an error containing

"indexed into non-array"if not.Check that the indexing expression is a number. Signal an error containing

"index not a number"if not.Check that the index number is a valid index for the array value —

that is, it is between 0and the stored number of elements in the array minus one. Signal an error containing"index out of bounds"Evaluate to the array element at the specified index.

These same error messages apply also to setting the value of an array.

You can do this with just rax, but it causes some

pain. Feel free to use as scratch registers r13 and r14 as

needed (for example saving the index in r14 and using rax

to store the address of the tuple). This can save a number of

instructions. Note that we will generate code that doesn’t need to

use r13 or r14 beyond the extent of this one expression,

so there is no need to worry about saving or restoring the old value

from r14 except in the compilation of the main expression.

You also may want to use an extended syntax for mov in order to combine these

values for lookup. For example, this kind of arithmetic is allowed inside

mov instructions:

mov rax, [rax + r14 * 8 + 8]This would access the memory at the location of rax, offset by

the value of r14 * 8 + 8. So if the value in r14 were,

say 2, this may be part of a scheme for accessing the second

element of a tuple. To aid in this we have generalized the

MemRef type to allow for these dynamically computed offsets:

struct MemRef {

reg: Reg,

offset: Offset,

}

enum Offset {

Constant(i32),

Computed { // reg * factor + constant

reg: Reg,

factor: i32,

constant: i32,

},

}Neither R14 nor anything beyond the typical

Offset::Constant is required to make this work, but you

may find it simpler to compile using these.

4.3 General Heap Layout

The register r15 has been designated as the heap pointer. The

provided stub.rs has a large global HEAP array and

passes a pointer to the resulting address as an argument to

start_here. The support code provided fetches this value (as a

traditional argument), and stores it in R15. It is up to your

code to ensure that the value of R15 is always the address of

the next block of free space (in increasing address order) in the

provided block of memory.

4.4 Interaction with Existing Features

Any time we add a new feature to a language, we need to consider its interactions with all the existing features. In the case of Egg-eater, that means considering:

If expressions

Function calls and definitions

Tuples in binary and unary operators

Let bindings

Typing rules

We’ll take them one at a time.

If expressions: Since we’ve decided to only allow booleans in conditional position, we simply need to make sure our existing checks for boolean-tagged values in if continue to work for tuples.

Function calls and definitions: Tuple values behave just like other values when passed to and returned from functions —

the tuple value is just a (tagged) address that takes up a single word. Tuples in let bindings: As with function calls and returns, tuple values take up a single word and act just like other values in let bindings.

Tuples in binary operators: The arithmetic expressions should continue to only allow numbers, and signal errors on tuple values. There is one binary operator that doesn’t check its types, however:

==. We need to decide what the behavior of==is on two tuple values. Note that we have a (rather important) choice here. Clearly, this program should evaluate totrue:let t = [4, 5] in t == tHowever, we need to decide if

[4,5] == [4,5]should evaluate to

trueorfalse. That is, do we check if the array addresses are the same to determine equality, or if the array contents are the same. For this assignment, to get some practice traversing the heap, we will take the latter approach, which requires a traversal of the arrays. Rather than write this in assembly, you should make a new function instub.rsto help you. Your implementation does not need to be robust in the presence of cycles in the heap or overflowing the Rust stack.To help you working with raw bytes in Rust, we have provided a function

load_snake_arraythat takes a pointer to an array in the heap and "parses" it into a struct consisting of a size and a pointer to the first element of the array. You can then access the other elements of the array by using the.add(n)method on pointers. You will need to useunsafecode to implement this, of course.Tuples in unary operators: The behavior of the unary operators is straightforward, with the exception that we need to implement

printfor tuples. We could just print the address, but that would be somewhat unsatisfying. Instead, we should recursively print the tuple contents, so that the programprint([4, [true, 3]])actually prints the string

"[4, [true, 3]]". This will require some additional work with pointers instub.rs. A useful hint is to create a recursive helper function forsprint_snake_valthat traverses the nested structure of tuples and prints single values. Again,printshould work properly for all acyclic tuples of reasonable depth, but does not have to be robust in the presence of cycles or overflowing the Rust stack.

5 Recommended TODO List

To start, get your compiler pipeline working on your old test cases by putting

panic!in any spot that uses a new feature such as an array or a complexlet.Extend your sequentialization function to handle the

Array,ArraySetcases. These should be similar to the cases you’ve implemented before.Get array creation and access/set working for arrays containing two elements, testing as you go. This is very similar to the pairs code from lecture.

Implement the new the unary operators to handle arrays appropriately and update old primitives if necessary to accomodate arrays (it may be useful to make version of

printand==that simply print the address and compare addresses before implementing the full version). Test as you go.Make tuple creation and access/set work for tuples of any size. Test as you go.

Tackle

printfor tuples if you haven’t already. Test as you go.Tackle

==for tuples as a function in Rust. Test as you go. Implementing print first should helpTry implementing an interesting test cases using lists, binary trees or another interesting recursive datatypes in Egg-eater. Include one of these examples as

interesting.eggin theexamples/directory.

6 List of Deliverables

your

compile.rsandasm.rsthe other src/*.rs files in the starter code

any additional modules you saw fit to write

your

runtime/stub.rsthe Cargo.toml

integration tests (

tests/examples.rs)your test input programs (

examples/*.eggfiles)

Again, please ensure cargo builds your code properly.

The autograder will give you an automatic 0 if they cannot compile your code!

7 Grading Standards

For this assignment, you will be graded on

Whether your code implements the specification (functional correctness),

the comprehensiveness of your test coverage

8 Submission

Wait! Please read the assignment again and verify that you have not forgotten anything!

Please submit your homework to gradescope by the above deadline.