Assignment 9: Fer-de-lance: Anonymous, first-class functions

Due: Wed 12/15 at 9pm

git clone

For this final compiler addition you’ll implement Functions Defined by Lambdas.Click here for scary snake picture!

There is relatively little starter code this time. Note that register allocation is optional for this assignment.

(At the time of release, the gradescope autograder isn’t up yet, but will be by sometime Friday 12/03).

1 Language

1.1 Syntax

Fer-de-lance starts with the same semantics as Egg-eater, and makes four significant changes:

It adds the notion of a lambda expression for creating anonymous function values.

The function-position in an application expression may now be any expression, not just an identifier.

Support for mutually recursive function definitions has been removed.

The old function definition syntax can now be used to define recursive functions anywhere inside an expression.

Before all function definitions had to be at the top level, but now we can write things like

let x = 3 in

def f(y):

x * y

end

x + f(x)

This means we no longer have a Prog and Exp distinction,

we’re back to only dealing with Exp.

pub enum Exp<Ann> {

Call(Box<Exp<Ann>>, Vec<Exp<Ann>>, Ann),

Lambda {

params: Vec<String>,

body: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

RecLambda {

name: String,

params: Vec<String>,

body: Box<Exp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

}

pub enum SeqExp<Ann> {

Call(ImmExp, Vec<ImmExp>, Ann),

Lambda {

params: Vec<String>,

body: Box<SeqExp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

RecLambda {

name: String,

params: Vec<String>,

body: Box<SeqExp<Ann>>,

ann: Ann,

},

}The concrete syntax of lambda expressions requires that you

write end after the body, similar to the def syntax:

let add = (lambda x, y: x + y) in

add(5, 6)1.2 Semantics

Functions should behave just as if they followed a substitution-based semantics. This means that when a function is constructed, the program should store any variables that they reference that aren’t part of the argument list, for use when the function is called. This naturally matches the semantics of function values in languages like Rust and Python.

There are several updates to errors as a result of adding first-class functions:

There is no longer a well-formedness error for an arity mismatch. It is a runtime error (that should report "wrong number of arguments", at least).

The

ValueUsedAsFunctionerror is no longer a static error. If you call something that is not a function, it should report an error at runtime including the string "called a non-function"The

DuplicateFunName, andUndefinedFunctionerrors are removed andFunctionUsedAsValueerrors are no longer used.There should still be a (well-formedness) check for duplicate argument names, but there is, naturally, no longer a check for duplicate function declarations. (This will be covered by the normal shadowing check for repeated bindings of a name.)

2 Implementation

2.1 Memory Layout and Function Values

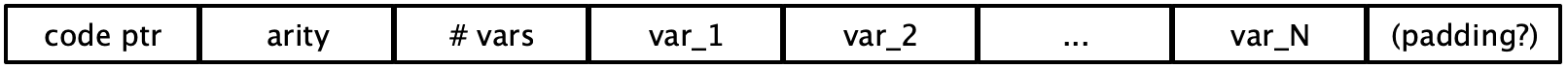

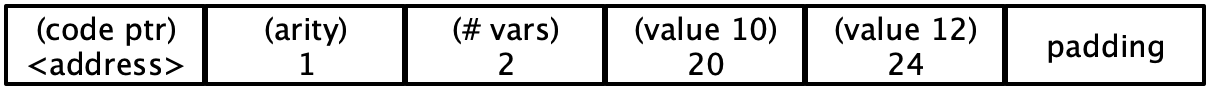

Functions are stored in memory with the following layout:

For example, in this program:

let x = 10 in

let y = 12 in

let f = lambda z: x + y + z end in

f(5)The memory layout of the lambda would be:

There is one argument (z), so 1 is stored for arity. There are two free

variables—x and y—20 to represent 10 and 24 to represent 12).

It is your choice whether to store the arity and the number of free variables as raw

numbers or as Fer-de-lance numbers (i.e. as 1 and 2 or as 2

and 4) —

Function values are stored in variables and registers as the address

of the first word in the function’s memory, but with an additional 0x3

(0b011 in binary) added to the value to act as a tag.

The value layout is now:

Bit pattern |

| Value type |

|

| Number |

|

| True |

|

| False |

|

| Tuple |

|

| Function |

2.2 Computing and Storing Free Variables

An important part of saving function values is figuring out the set of

variables that need to be stored, and storing them on the heap. Our compiler

needs to generate code to store all of the free variables in a function —x is free and y is not in:

lambda y: x + y endIn this next expression, z is free, but x and y are not, because x is

bound by the let expression.

lambda y: let x = 10 in x + y + zNote that if these examples were the whole program, well-formedness would signal an error that these variables are unbound. However, these expressions could appear as sub-expressions in other programs, for example:

let x = 10 in

let f = lambda y: x + y end in

f(10)In this program, x is not unbound —let. However, relative to the lambda expression, it is free, since

there is no binding for it within the lambda’s arguments or body.

You will need to design and write a function free_vars that takes a

SeqExp and returns the set of free variables.

For example, this might have the type

fn free_vars<Ann>(e: &SeqExp<Ann>) -> Vec<String>You may consider passing in the current parameters as an extra

argument, and you may need to write one or more helper functions that

keep track of an environment. Then free_vars can be used when

compiling Lambda to fetch the values from the surrounding

environment, and store them on the heap. In the example of heap

layout above, the free_vars function should return ["x",

"y"], and that information can be used to perform the necessary

mov instructions. Note that you really want to return a

set, with no duplicates. You may want to use HashSet

for this.

This means that the generated code for a lambda will look much

like it did before, but with an extra step to move the stored

variables:

jmp after1

temp_closure_1:

<code for body of closure>

after1:

mov [R15 + 0], temp_closure_1

mov [R15 + 8], <arity>

mov [R15 + 16], <number of captured free variables>

mov [R15 + 24], <var1>

... and so on for each variable to store

mov RAX, R15

add RAX, 3

add R15, <heap offset amount>2.3 Restoring Saved Variables

The description above outlines how to store the free variables of a function. They also need to be restored when the function is called, so that each time the function is called, they can be accessed.

In this assignment I suggest you treat the stored variables as if they were a special kind of local variable, and store them in the appropriate register or stack slot at the beginning of each function call. So each function body will have an additional part of the prelude that restores the variables, and their uses will be compiled just as local variables are. This lets you re-use much of our infrastructure for local variables.

The outline of work here is:

At the top of the function, get a reference to the address at which the function’s stored variables are in memory

Add instructions to the prelude of each function that restore the stored variables onto the stack/register, given this address

Assuming this stack layout, compile the function’s body in an environment that will look up all variables, whether stored, arguments, or let-bound, in the correct location

The second and third points are straightforward applications of ideas we’ve

seen already —

The first point requires a little more design work. If we try to fill in the

body of temp_closure_1 above, we immediately run into the issue of where we

should find the stored values in memory. We’d like some way to, say, move the

address of the function value into RAX so we could start copying values onto

the stack:

temp_closure_1:

<usual prelude>

mov RAX, <function value?>

mov R14, [RAX + 21] ;; NOTE: why 21?

mov [RBP - 16], R14

mov R14, [RAX + 29] ;; NOTE: why 29?

mov [RBP - 24], R14

... and so on ...But how do we get access to the function value? The list of instructions for

temp_closure_1 may be run for many different instantiations of the function,

so they can’t all look in the same place.

To solve this, we are going to augment the calling convention in Fer-de-lance

to pass along the function value when calling a function. That is, we will

push one extra time after pushing all the arguments, and add on the function

value itself from the caller. So, for example, in a call like:

f(4, 5)We would generate code for the caller like:

mov RAX, [RBP-8] ;; (or wherever the variable f happens to be)

<code to check that RAX is tagged 0b011, and has arity 2>

push 8

push 10

push RAX ;; BE CAREFUL that this is still the tagged value

mov RAX, [RAX] ;; the address of the code pointer for the function value

call RAX ;; call the function

add RSP, 24 ;; since we pushed two arguments and the function value, adjust RSP by three slotsTo support jumping and adding to locations stored in a register, all

Jmp and Call Instrs now take a JmpArg that

can be a label or a register.

(Note: Be careful when implementing tail-calls to functions now, since their arity is now one less than the number of stack slots actually needed...)

Now the function value is available on the stack, accessible just as the first argument

argument (e.g. with [RBP + n]), so we can use that in the prelude for

copying all the saved variables out of the closure and into their more typical

local-variable stack slots:

temp_closure_1:

<usual prelude>

mov RAX, [RBP + n] ; load the closure into rax

mov R14, [RAX + 21]

mov [RBP - 16], R14

mov R14, [RAX + 29]

mov [RBP - 24], R14

... and so on ...In recursive functions, you should just be able to treat the function

itself as the first parameter. To avoid code duplication, you might

want to desugar Lambda into RecLambda with a function

name you know won’t occur.

For printing function values, you can simply print function or

you can print out the address and the values of the free

variables. For (dis-)equality checking, functions are not equal to

things with different tags, and equality of functions is unspecified,

one choice is pointer equality and another is to always return false,

since it is impossible to tell if two functions have the same

behavior.

3 Recommended TODO List

Move over code from past assignments and/or lecture code to get the basics going. There is intentionally less support code this time to put less structure on how errors are reported, etc. Note that the initial state of the tests will not run even simple programs until you get things started.

Implement sequentialize for

Lambda,RecLambda.Implement the compilation of

Lambda,RecLambdaandCall, ignoring stored variables. You’ll deal with storing and checking the arity and code pointer, and generating and jumping over the instructions for a function. Test as you go.Implement

freevars, testing as you go.If doing register allocation, update your liveness and conflict functions to account for functions with free variables. You should ensure that all free variables in a lambda are considered conflicting.

Implement storing and restoring of variables in the compilation of

Lambda,RecLambda, and andCall

4 List of Deliverables

your

compile.rsandasm.rsthe other src/*.rs files in the starter code

any additional modules you saw fit to write

your

runtime/stub.rsthe Cargo.toml

integration tests (

tests/examples.rs)your test input programs (

examples/*.eggfiles)

5 Grading Standards

For this assignment, you will be graded on

Whether your code implements the specification (functional correctness),

the comprehensiveness of your test coverage

6 Submission

Wait! Please read the assignment again and verify that you have not forgotten anything!

Wait! Please read the assignment again and verify that you have not forgotten anything!

Please submit your homework to gradescope by the above deadline.